I think most of what is called “elitist” is a mask for anti-intellectualism — I mean, there is such a thing as excellence.

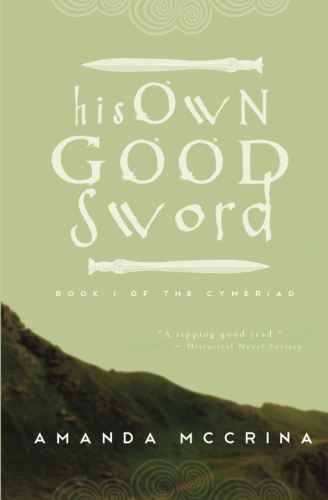

The above is from a 1992 interview with Susan Sontag, the transcript of which I read here. It’s a great interview filled with wonderful reflections on writing and literature and it touches on something I’ve been thinking about for a while—ever since I decided to self-publish His Own Good Sword, possibly ever since I started thinking seriously about publishing at all. There is indeed a strong anti-elitist current running through the modern literary landscape, exacerbated and best illustrated by the boom in self-publishing and the exploding popularity of events like NaNoWriMo (which last year had nearly 400,000 participants worldwide), but by no means limited to the ranks of self-published writers. Words like “elitism” and “gatekeepers” connote stuffiness and obsolescence. To be elitist is to be out-of-touch with the state of modern publishing. After all, writing is democratic: everyone should have the right to express their creativity in words.

The problem is that when you write—and especially when you choose to make your words known to the world—you’re entering into a great conversation that’s been going on for thousands of years. While it’s not mandated by some sort of Writing God that you pay careful attention to what’s gone before you, what’s already been said, it certainly makes you seem presumptuous when you don’t—when you consider yourself ready to engage in the discussion with a minimum of preparation or with no preparation at all. Everyone has the right to write, but with that right comes responsibility: to listen, to learn, to be aware of your context, above all to read, and especially the classics (and not just the 20th-century classics; the roots of contextualization need to go much deeper).

As writers we’re told constantly to be immersed in our market. This means reading what’s currently popular, particularly in our chosen genre. This is problematic. This is equivalent to building an economy around one export item, making yourself entirely dependent on that item; and then when the demand shifts or you’ve used up all your resources you’ve got nothing to fall back on. Essentially writers need to diversify if they want staying power. (There’s absolutely no reason you shouldn’t be reading Dostoevsky and Tolstoy if you write YA contemporary. If you argue that there is, perhaps it says more about the state of YA contemporary than anything else.)

If it’s elitist to argue that writers should strive for contextual awareness in the landscape of literature, then I have to admit I’m elitist. But in all honesty it’s remarkably humbling to realize your place in the conversation.