I always hesitate to call my writing fantasy, because I know that gives people the wrong impression. I’m more often tempted to call it historical fiction, because that seems easier to explain and defend. There is no magic in my imaginary world. There are no fantastical creatures. There’s nothing, in fact, that would be implausible in real-world historical fiction. And I labor to create a sense of “historical” realism. It’s not real history; what I mean is that my characters’ identities derive from their past, the same as do our identities in our world. The way their world works—and the way they understand it to work—is linked inextricably to their history.

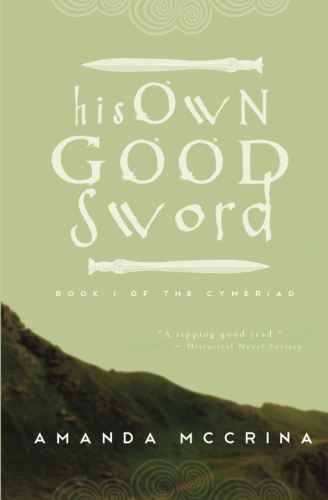

My characters are products of their environments. Their stories don’t happen in a vacuum; their societies have long histories, long memories. I want the reader to feel their world is an internally coherent one, and a complex one; I want the reader to have the sense that myriad other stories are happening concurrently with yet independently of my characters’ stories. So I have to give thought to the economic and monetary systems, the climate and crops and markets, the language, the literacy rate, the social issues at work in the background. Perhaps none of this is a pivotal or even visible element in a particular story, but it’s there as an important part of the framework just the same. I want there to be a reason (besides plot convenience) why my main character in Blood Road is bilingual. I want there to be a reason why the royal family are the only ones allowed to wear sapphires. I want there to be a reason why my Empire would wage war over an economically and strategically unimportant rural province in His Own Good Sword. I don’t want anything to feel arbitrary.

Obviously (unsurprisingly) my fantasy world owes a great deal to real-world history, particularly Roman history. With some careful carving-up His Own Good Sword and its prequel, Blood Road, my current WIP, may have worked very well as historical fiction set in the late, crumbling, Christianized Empire. I write very consciously with that setting in mind, because it’s what I know and love. But I choose to write it as “fantasy.” Why? What exactly is fantasy, anyway?

As I said above, “fantasy” has the wrong connotation, if not technically the wrong definition. Technically, any fiction is a sort of fantasy—an imagining of what could be or what might have been. The World English Dictionary defines “fantasy” simply as “imagination unrestricted by reality.” Rather than using “fantasy” as my sandbox for playing with magic and the supernatural, then, I am using it to play with questions of politics and ethics and philosophy. My writing is probably best called “historical fantasy” or “political fantasy”—but even those terms trip people up, because the assumption remains that magic has something to do with it. Mine is neither a real-world setting infused with supernatural elements (as Naomi Novik’s Temeraire series, or Katy Moran’s Bloodline), nor a supernatural world with the trappings of real-world history (as Megan Whalen Turner’s Queen’s Thief series, or Guy Gavriel Kay’s Tigana). The “fantasy” comes instead from exploring real-world issues—slavery, racial and class prejudice, political corruption, theories of government—in a setting informed but unrestricted by reality. It’s magic-less, but it’s no less fantasy.